The return of the monarchy with Charles II in 1660 not only led to the reopening of theatres, but also brought innovations such as women taking to the stage. David Evans sets the scene

It is, perhaps, not well-known that the return to public theatrical production in Westminster – and in London as a whole – with the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 was preceded by two such events in 1658 and 1659, before the puritanical Cromwellian regime collapsed.

London theatres were closed in 1642, but the tradition of drama was maintained by ad hoc illicit performances in inns and at fairs, and occasional private performances, such as Sir William Davenant’s The Siege of Rhodes presented at the home of the Dowager Duchess of Rutland in Charterhouse Square in 1656.

However, in 1658 the authorities allowed public performances of another musical entertainment – Davenant’s The Cruelty of the Spaniards in Peru – at the disused Cockpit Theatre in Drury Lane and this was followed by his Sir Francis Drake, at the same venue, in 1659.

Because England had been at war with Spain since 1655, these were probably permitted as excellent examples of anti-Spanish propaganda, and it is interesting to speculate whether such entertainments would have been a prelude to even more had the Restoration not taken place.

Restoration brought theatrical innovation in its trail, as Samuel Pepys found when in early January 1661 he went to the Vere Street Theatre – situated in part of today’s Aldwych area – to see a play entitled Beggar’s Bush. He noted in his diary that this was ‘the first time that ever I saw women come upon the stage’.

This theatre was used by a group of players formed by the playwright Thomas Killigrew who had once been page to King Charles I and was a Groom of the Bedchamber to King Charles II.

In 1662, he and William Davenant were granted the sole right to present theatrical productions in London. Killigrew’s Company was known as the King’s Company and Davenant’s was the Duke of York’s Company. By 1663, Killigrew had established his players in what was to become the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and Davenant settled his at a venue near Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

The 1660s brought other innovations such as the picture-frame or proscenium arch stage and moveable scenery – both already known on the continent. The arch framed the back of the stage, but a wide apron was still projected out into the auditorium much as it had done in the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras.

Generally, scenery consisted of painted backdrops with side flats that slid in grooves when a scene was to be changed. On occasions, machinery was used so that gods and other supernatural beings could descend into the action of a play.

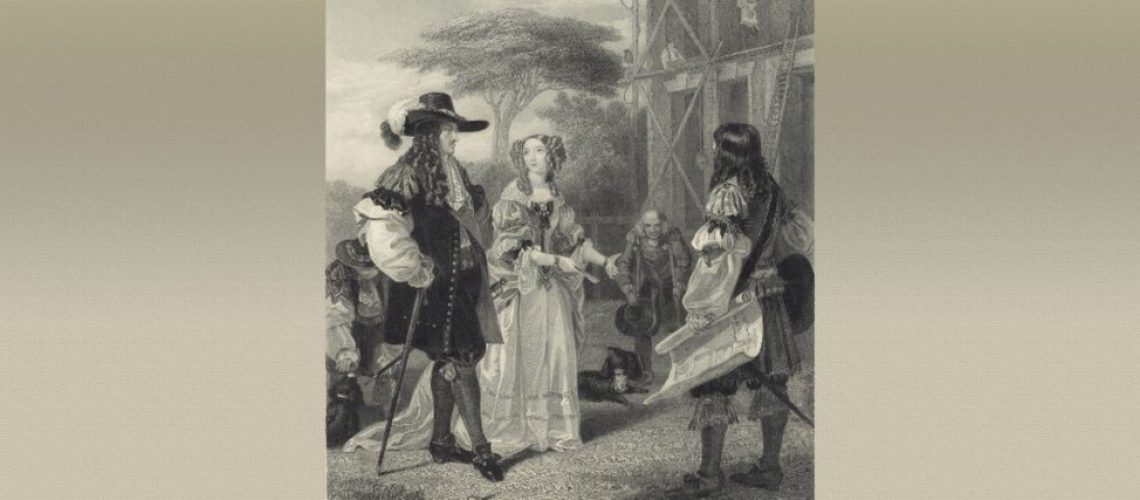

The new era also brought in a group of talented actors, one of whom was Nell Gwyn. Despite her limitations in dramatic roles, Nell was extremely popular in comic parts and she was certainly very popular with King Charles II, whose mistress she became later in the decade – not a bad outcome for one who had started her rise to fame as a lowly orange seller at the Drury Lane Theatre.

Foreign visitors to London were often favourably impressed by what they saw in the capital’s theatres. For example, in 1663 a French playgoer in London, Balthasar de Montconys, thought it was the cleanest and nicest theatre he had ever seen and accordingly described the playhouse as ‘le théâtre le plus propre et le plus bien que j’ai jamais vu’.

How clean and decent it really was is arguable because in the Restoration theatre playgoers often talked throughout performances, rowdiness was not unknown and the fug of tobacco smoke, the smell of peeled oranges and the abundance of unwashed bodies in the audience must have made a visit to the theatre something of a trial for some. On the other hand, Montconys’s comments could mean that French theatres and audiences were much worse than those on this side of the Channel.

So, as the prelude of 1658-1659 morphed into the first act of the Restoration theatre of the 1660s, who could have dreamt of the glories that lay ahead with such names as Congreve, Dryden, Vanbrugh, Wycherley and Aphra Behn all waiting in the wings to embellish the rich theatrical era which had, unknown to those at the time, started with The Cruelty of the Spaniards in Peru and Sir Francis Drake?

Image: Nell Gwyn in a scene from the Legend of Chelsea Hospital (published 1845 by Joseph Hogarth after unknown artist) (National Portrait Gallery, London)