Three years after the end of the Blitz, Westminster was once again in the front line

By Mark Lubienski

Dr. Reginald Victor (R. V.) Jones was the scientist in charge of British technical intelligence during the Second World War, holding the position of Assistant Director of Intelligence (Science). Just after 11am on the morning of Sunday 18th June 1944, Jones was speaking on the telephone in his office at 54 Broadway – the headquarters of the British Secret Intelligence Service, MI6 – when he heard the unmistakable drone of a flying bomb. Suddenly the engine cut out and seconds later a deafening explosion close-by rocked the building.

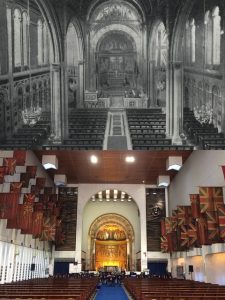

Quickly leaving the building, rushing round the corner along Queen Anne’s Gate and into Birdcage Walk, Jones witnessed “one of those sights one doesn’t forget. The whole of Birdcage Walk was a sea of plane tree leaves”. Walking further, he later recalled that “I went on as far as the Chapel, saw that the corner of the Chapel had been hit, and by the time I got there the Guards were beginning to carry out their dead”.

R. V. Jones was describing the aftermath of the destruction of the Guards’ Chapel at Wellington Barracks, which had just been hit by a V1 flying bomb, one of Adolf Hitler’s so-called ‘Vengeance Weapons’ also known as the ‘Doodlebug’. The Sunday morning service had been in progress and the building was packed with servicemen, civilians, and their families. Moments later, one hundred and twenty-one people lay dead beneath tons of fallen masonry ten feet deep in places, with many more injured in the most devastating attack of what became known as ‘Doodlebug Summer’. Only the apse and altar of the Chapel remained intact and the operation to free survivors took another 48 hours. But despite the damage, part of the Chapel was re-opened in time to hold services that Christmas. Rebuilt on the same site in 1963, it incorporated the original apse at the east end of the Chapel and featured an engraved wall memorial by the west entrance recording the names of all who died in the 1944 attack.

Rolling back five years to November 1939, and R. V. Jones was ensconced in his office at 54 Broadway when his good colleague, Group Capt. Frederick Winterbotham, dumped a small parcel on his desk announcing “Here’s a present for you!”. It had come via the British Naval Attaché in Oslo and contained a typed seven-page report and a glass fuse. That document, written by a leading German scientist, would turn out to be one of the most spectacular intelligence leaks in history. It contained details of advanced research and development in German radar, navigation systems, fuses, gliders and torpedoes, and became known as the Oslo Report. But three words in particular caught Jones’ scientist’s eye; ‘missiles’ and ‘rocket propulsion’. The report also mentioned a secret experimental facility on Germany’s Baltic coast previously unknown to British Intelligence; Peenemünde. Incredibly, intelligence chiefs believed the report was both a hoax and a plant so discarded their copies. But the astute Jones was convinced and even though he initially failed to persuade others, he was certain that it was an invaluable resource. And so it proved. Years later he remarked that “…in the few dull moments of the War, I used to look up the Oslo Report to see what should be coming along next”.

Over the next five years, Winston Churchill would increasingly rely upon R. V. Jones’ expertise and judgment and he would come to play a pivotal role in British efforts to discover the truth about Nazi Germany’s long-range weapons program. That campaign against research and development, manufacturing and transportation, launch sites and even against missiles in flight, would become known as Operation Crossbow. And so it was that in late November 1943 the existence of a pilotless pulse-jet powered aircraft, carrying a warhead of around one ton, was finally confirmed through the work of the brilliant photo interpreters at RAF Medmenham in Buckinghamshire. Nonetheless, by the end of May 1944 no V1 strikes had materialized, but imminent attacks were still expected.

Five days before the attack on the Guards’ Chapel, and just a week after the successful D-Day landings in Normandy, an unidentified aerial vehicle was spotted over Kent. It emitted a low, rhythmic drone “like a model T Ford going up a hill” and flew at a terrific speed with yellowish flames trailing behind it. In the pre-dawn hours of Tuesday 13th June, with London still asleep, it struck a railway bridge in Bethnal Green, east London, killing six people and leaving two hundred homeless, while schoolboys swiftly scoured the crash site for souvenirs. Media censorship meant that the Evening Standard reported only that “bombs fell in a working class area”, while the BBC mentioned that an enemy raider had been shot down “somewhere over London”. It was the only one of ten V1 flying bombs launched in the first wave to hit London, but the first of 2,419 to strike the capital during the summer of 1944 killing over six thousand people.

The V1 that destroyed the Guards’ Chapel a few days later on Sunday 18th June wasn’t the only such incident in Westminster that day. Earlier in the morning a V1 struck the side of Hungerford railway bridge damaging a track. Another plunged into Rutherford Street at the north-east corner of Vincent Square killing ten civilians, demolishing two blocks of flats, but fortunately also leaving behind parts of its casing and detonator which were swiftly removed by military personnel and rushed to R. V. Jones and his team of boffins for examination. Over the next few days Westminster would suffer several more V1 strikes, including one right by Victoria Station, but the next major incident came on Friday 30th June. Early that afternoon the Aldwych was packed with people going about their daily business and enjoying their lunch hours, when a V1 exploded in the middle of the road between BBC Bush House and Adastral House, the headquarters of the Air Ministry on the corner with Kingsway. The foyer of the Aldwych Theatre was destroyed, Australia House suffered serious damage, two double-decker buses were ripped apart and forty-six people perished in that strike.

After a few more weeks the success of air defences in the south of England, and the capture of launch sites in northern France and Belgium, meant that by the end of August 1944 V1 attacks had tailed off drastically; fewer than one in ten of the flying bombs were now making it through to their target. The Minister of Information, Brendan Bracken, and the Chairman of the Crossbow Committee, Duncan Sandys, felt sufficiently confident to announce at a press conference on 7th September that “Except for a few shots, the battle of London is over.” But at 6.44pm the following evening, a massive explosion occurred in a leafy residential road in Chiswick, west London. There had been no ominous drone or any warning, three people were killed and six houses demolished, and a crater 30 feet wide and 8 feet deep was left behind. Hitler’s second ‘Vengeance Weapon’, a liquid-fuel powered rocket even more sinister and terrifying than the V1, caused the destruction; it was the world’s first ballistic missile and it was called the V2.

The ‘Battle of London’ would continue for another six months, with several V2 rockets hitting the heart of Westminster including the north-east corner of Hyde Park right by Speakers’ Corner and the Red Lion pub in Duke Street opposite Selfridges. But the work of R. V. Jones and many other dedicated men and women had provided a vital edge that would not be relinquished, so the Nazi flying bomb and rocket programs never reached their full potential during the war. After the war, however, would prove to be a different story when the same German scientists whose V2 rockets rained terror on London developed, and built, the Saturn V rocket that in 1969 put the first man on the moon.

Mark Lubienski is a Westminster Guide from the Class of 2014. He is also a co-founder of London War Walks, and gives occasional talks on the secret world of intelligence and espionage.

Twitter: @marklubienski Website: http://londonwarwalks.com/about/

© Mark Lubienski 2018